Triage #

Sudden or severe hypoxaemia requires emergency response.

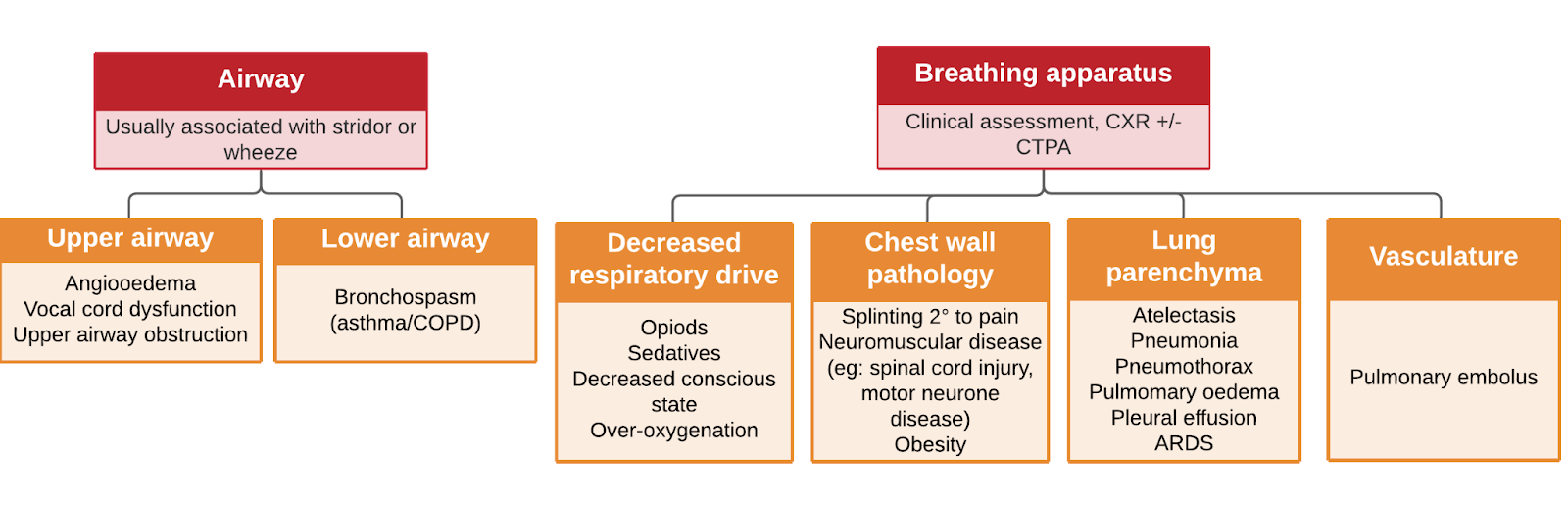

Classification #

Hypoxaemia without hypercapnia is termed type 1 respiratory failure.

Hypoxaemia with hypercapnia is termed type 2 respiratory failure.

An arterial blood gas is required to differentiate the two, where arterial pCO2 >45 mmHg indicates type two respiratory failure.

Causes #

Remember to take into consideration baseline respiratory function, both to understand the current presentation in context and identify those at risk of rapid deterioration

- Confirm the patient’s baseline/normal SpO2

- Check previous lung function tests and chest imaging

If present, hypercapnia indicates relative hypoventilation

- Hypercapnia may be longstanding in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome or chronic lung disease.

- A clue that a patient is chronically hypercapnic is a chronically elevated HCO3 (on the UEC) – this can indicate metabolic compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis.

- Respiratory acidaemia (ie: pH < 7.35 and pCO2 >45 on the blood gas) requires urgent senior assessment and management with ventilatory support.

Investigations #

- ECG

- Chest x-ray

- consider need for an urgent bedside exam rather than sending the patient down to radiology in a low acuity environment

- Consider

- FBE, CRP (?infection)

- BNP, troponin (?myocardial ischaemia/heart failure)

- D-dimer, CT pulmonary angiogram (?PE)

- Arterial blood gas (a helpful guide to ABGs here)

- COVID test (follow your institutions guidelines)

Management #

Use DRSABCD approach

Call a MET call if

- Severe hypoxaemia

- Altered conscious state

- Haemodynamic instability

- You are worried

Call a CODE BLUE if

- There is airway obstruction

- You suspect tension pneumothorax

- The patient has a tracheostomy

- The patient isn’t breathing

While you’re waiting for assistance, provide oxygen via a bag valve mask, connected to 15lpm wall oxygen.

| Airway | Suction any secretions/vomitChin lift/jaw thrust to open airway (if required call code blue)Note presence or absence of stridorStridor suggests impending airway obstruction, consider code blue |

| Breathing | Measure SpO2if <92% apply or increase supplemental oxygen whilst continuing your assessmentCount respiratory rate Assess work of breathingTripodingAccessory muscle useParadoxical abdominal breathingIntercostal muscle retractionAuscultate, specifically checking forPresence of breath sounds (?pneumothorax, pleural effusions)Crepitations (?pneumonia, atelectasis, pulmonary oedema, fibrosis, ARDS)Wheeze (?bronchospasm)Check chest drains, if presentAre they kinked? – unkink themAre they on suction? – if not, check if they should beIs there swinging? (indicates the drain is in the pleura and patent)Is there bubbling? (indicates ongoing gas leak from lung) |

| Circulation | Check HR and BPAssess tissue perfusion (are their hands/feet warm or cold?) |

| Disability | GCS -> If drowsy or reduced conscious stateCall METCheck drug chart for opiods/sedatives (these can potentially be reversed with naloxone and/or flumazenil, although this should be done with senior support)Check BSLAssess painDo they look like they are tiring from increased work of breathing? |

| Exposure | Head to toe examinationCheck calves for obvious signs of DVT |

Management of hypoxaemia involves

- providing supplemental oxygen (see below)

- treating the underlying cause

- considering concomitant hypercapnia (ie: type 2 respiratory failure). Where present:

- seek urgent senior support – hypercapnia can indicate severe disease, tiring and/or the need for NIV

- avoid overdosing supplemental oxygen – see below

- be mindful of the that hypercapnia itself can be a marker of deterioration, even if the hypoxaemia improves with supplemental oxygen

Providing supplemental oxygen #

- Is it important to set and document an appropriate SpO2 target

- 92-96% for most patients

- 88 – 92% for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, eg: COPD, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, severe chronic respiratory failure

- Supplemental oxygen is usually not indicated if SpO2 is >92%

- exceptions to this include CO poisoning, haemoglobinopathy and severe anaemia1

- Most patients on the ward won’t require more than 1-4lpm supplemental oxygen via nasal prongs. Patients requiring greater than 4lpm supplemental oxygen should be reviewed by a senior doctor

- Options for providing >4lpm supplemental oxygen include:

- Hudson mask (usually a short term solution)

- High flow nasal prongs (usually requires involvement of respiratory or ICU)

- CPAP or BiPAP (usually requires involvement of respiratory or ICU)

- Intubation

- Patients failing to meet target SpO2 despite high flow nasal oxygen therapy require urgent review by a senior doctor. Failing HFNP usually indicates a need for intubation (not NIV)2

Oxygen toxicity #

Oxygen toxicity (overdose) is a real and underappreciated phenomenon. Overshooting target oxygen levels can:

- worsen gas exchange by hampering physiological hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (worsening V/Q matching)

- exacerbate atelectasis (by washing out nitrogen)

- mask deterioration

- trigger cerebral and coronary vasoconstriction

References #

1. Beasley, R., Chien, J., Douglas, J., Eastlake, L., Farah, C., King, G., Moore, R., Pilcher, J., Richards, M., Smith, S. and Walters, H. (2015), Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen guidelines for acute oxygen use in adults: ‘Swimming between the fl ags’. Respirology, 20: 1182–1191. doi: 10.1111/resp.12620

2. Kang, B.J., Koh, Y., Lim, CM. et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med 41, 623–632 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3693-5

Contributors

Reviewing Consultant/Senior Registrar

Dr Scott Santinon

Dr Belinda Liu