Overview #

This guideline will primarily focus on an acute exacerbation of COPD, with some references to stable COPD management.

Definitions:

An exacerbation of COPD is characterised by the following:

- A change in the patient’s baseline symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, sputum) that is beyond day to day variation;

- is acute in nature;

- and may indicate a need for hospital admission or change of regular medications (1)

Key points: (1)

- Exacerbations of COPD are common

- Bronchodilators should form the initial management of an acute exacerbation

- systemic steroid therapy is effective at reducing length of hospital admission

- Aim oxygen saturations 88-92% in patients who are hypoxaemic

- Assess need for non-invasive ventilation (NIV) early in those with rising paCO2 levels to avoid poorer health outcomes

- Antibiotics are effective for an exacerbation of COPD with evidence of infection

- Consider multidisciplinary care and discharge planning on discharge

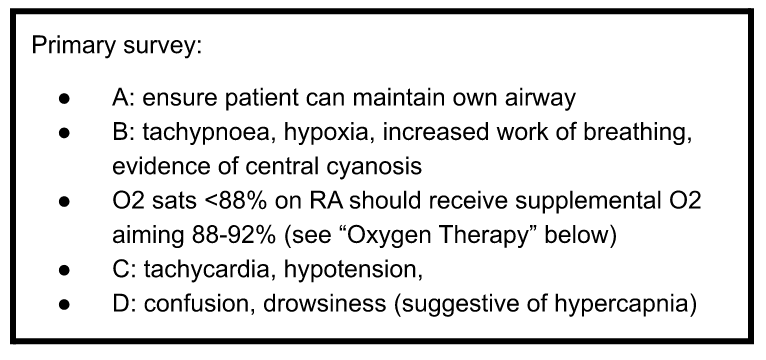

Triage #

Triaging acute exacerbations of COPD will depend on the clinical presentation:

- If hypoxic, tachypnoeic, signs of respiratory distress or drowsiness, should be seen immediately

- Otherwise, may be seen within one hour

Causes #

Precipitants of COPD exacerbations: (2)

- Infection (30-50%)

- Bacterial: haemophilus influenzae, streptococcus pneumoniae, moraxella catarrhalis, staphlococcus aureus, pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Viral: rhinovirus, adenovirus, RSV, influenza, parainfluenza

- Atypical: mycoplasma pneumonia

- Eosinophilic inflammation (20%)

- Other (30%)

- Pollutants

- Poor medication adherence

- CCF (1)

- PE (1)

- Consider when absence of infective signs, and if chest pain/cardiac failure is present

- Pneumonia

- Psychosocial stressors

Differentials:

Please see guideline on “Tachypnoea/hypoxia” for relevant differentials.

Clinical features: #

COPD exacerbations classically involve an acute worsening of the patient’s baseline symptoms including dyspnoea, sputum increase, cough or features of right heart failure (3).

Examination:

- Signs of infection/sepsis

- Signs of RHF (cor pulmonale)

Investigations #

Initial investigations

| Investigation | Significance |

| ECG | Rule out cardiac causes including ACS and arrhythmia contributing to symptoms |

| FBE | Investigate for anaemia (contributing to SOB) and leukocytosis (infection) |

| UEC | Investigate for concurrent AKIElevated bicarbonate may suggest chronic respiratory acidosis |

| CXR | Investigate for pneumonia (changes antibiotic choices) or evidence of heart failure |

| Covid swab* | Important for any patient presenting with respiratory symptoms |

Further investigations

| Investigation | Indication |

| ABG* | Consider in patients with severe exacerbations of COPDMonitor for worsening hypercapnia which may indicate T2RF and need for RCU/ICU |

| Troponin T | Consider based upon patient comorbidities and presentation |

| CRP* | Consider if clinical presentation suggestive of infection/patient is septic on admission |

| D-dimer* | Consider if suspicion for PE and need to rule out. Alternatively can consider CTPA if high clinical suspicion and after liaison with senior medical staff. |

Other investigations:

| Investigation | Significance |

| Sputum MCS* | If suspicious of infection |

| Respiratory multiplex swab (NPA)* | Consider based upon suspicion for influenza |

| Spirometry* | Consider if patient has had no previous lung function testing (essential for diagnosis/staging of COPD) or no recent lung function test |

Note:. COPD patients often have colonisation of their respiratory tracts with pathogens including streptococcus pneumoniae, haemophilus influenzae and moraxella catarrhalis; consequently, a positive sputum culture may not reflect infection.

Management #

Consider whether the patient has an advance care directive in place which may guide goals of care.

Indications for Admission for Exacerbations of COPD: (1)

- Marked increase in intensity of symptoms

- Patient has acute exacerbation characterised by increased dyspnoea, cough or sputum production, plus one or more of the following:

- Inability to be managed in the community:

- Poor response to ambulatory management

- Unable to mobilise between rooms when previously able

- Unable to eat/sleep due to dyspnoea

- Unable to manage at home with home-care resources

- Severity of disease:

- Altered conscious state (suggestive of hypercapnia)

- Worsening/new hypoxaemia measured by pulse oximetry or cor pulmonale

- Newly occurring arrhythmia

- High risk comorbidities (either pulmonary or non-pulmonary)

- Inability to be managed in the community:

Bronchodilator therapy (3):

| First Line: | Salbutamol 100microg/actuation, up to 8 puffs (one at a time), inhaled via metered dose inhaler with spacer, repeated as necessary |

| Second Line: | terbutaline 500 micrograms per actuation, 1 or 2 actuations via dry powder inhaler, repeated as required OR (except patient currently on LAMA) ipratropium 21 micrograms per actuation, up to 4 actuations (one at a time) via pressurized metered dose inhaler with spacer, repeated as required |

| Note: high doses of salbutamol and terbutaline can lead to electrolyte abnormalities including hypokalaemia and hypomagnesemia (3-5), which may be worsened by concurrent hypoxia, diuretic and steroid use. Caution excessive use in those with cardiovascular disease due to risk of adverse cardiac effects (4-5). Note: ipratropium is contraindicated in patients already on a LAMA (6) |

Bronchodilator therapy is first line management for an acute exacerbation of COPD. Salbutamol, terbutaline and ipratropium all have similar efficacy in their effects on COPD; however, ipratropium has a slower onset of action and is contraindicated in patients using a LAMA (3).

If nebulisers are required:

| Salbutamol 2.5 to 5 mg by inhalation via nebuliser, as required OR (except patient currently on LAMA)ipratropium 250 to 500 micrograms by inhalation via nebuliser, as required. |

Evidence in asthma studies suggests similar efficacy in beta-agonists delivered via metered dose inhaler and spacer compared to nebuliser (6), although the applicability to COPD patients is not known. Nebulisers should be used in conjunction with compressed air opposed to oxygen to avoid hyperoxygenation of the patient (1).

Note that nebulisers are not commonly used in ward settings presently due to COVID and risk of aerosolisation, and thus are usually done within an ICU setting.

Systemic corticosteroids: (3)

| First Line: | Prednisolone 30 to 50mg, PO, daily for 5/7 |

| If oral steroids cannot be tolerated: | Hydrocortisone 50mg IV Q6H until oral intake is resumed |

Systemic steroid therapy has been demonstrated to improve lung function and symptoms, shorten length of inpatient stay and reduce the chance of failure of treatment. Total courses of steroids should equal five days with no need for tapering doses given short course (7).

Antibiotics:

Use if clinical suspicion for an infective exacerbation, characterised by the following: (8)

- increase in sputum production or change in colour

- increase in sputum purulence

- fever

| Amoxicillin 500mg PO Q8H for 5/7 OR (except patient currently on LAMA)Amoxicillin 1g PO BD for 5/7ORDoxycycline 100mg PO BD for 5/7 |

Note that if there is radiological evidence of pneumonia in a patient with COPD, antibiotic choices should follow the relevant pneumonia guidelines (8).

Oxygen Therapy:

Oxygen saturation (measure via pulse oximetry) targets should be between 88-92% in COPD patients who are hypoxaemic on presentation (noting this target only applies if the patient is a chronic CO2 retainer). Nasal cannula should be used with a rate of between 0.5-2L usually sufficient; avoid use of high flow via Hudson mask or non-rebreather, as this may lead to hypoventilation and worsening respiratory acidosis. (1) Over-oxygenation should be avoided in COPD patients has this has been associated with worse outcomes including acute respiratory failure and mortality (9).

Non-invasive Ventilation (NIV):

Noninvasive ventilation should be considered early in patient with acute respiratory acidosis, demonstrated by:

- pH < 7.35

- Hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mmHg)

Early NIV improves mortality outcomes, length of stay, and can reduce the need for intubation (10).

Other Considerations:

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Can be commenced during admission once patient is stable (1)

- Improves quality of life, exercise tolerance; reduce short-term mortality and COPD-related hospital admissions (1)

- Review of current puffer therapy

- Upgrade as per COPD-X guidelines as required

- Spacer inhalation technique and adherence

- Ensure vaccinations are up to date

- Updated COPD action plan

Suggested Criteria for safe discharge: (1)

- Clinically stable condition without need for parenteral therapy for over 24 hours

- Stretch of bronchodilators to over Q4H

- Cessation of supplemental oxygen therapy (unless on home O2 or home O2 is indicated)

- Return to previous functional baseline; able to perform regular ADLs, eat and sleep without significant dyspnoea

- Patient or caregiver understands medication regime and can effectively administer medications

- Follow up care (nursing, allied health, community services, home O2, GP) has been organised

References #

(1) Yang I, Dabscheck E, George J, Jenkins S, McDonald C, McDonald V, et al. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2020, Version 2.61. Milton, QLD: Lung Foundation Australia; February 2020.Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://copdx.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/COPDX-V2-63-Feb-2021_FINAL-PUBLISHED.pdf

(2) Kim V, Aaron SD. What is a COPD exacerbation? Current definitions, pitfalls, challenges and opportunities for improvement. European Respiratory Journal Nov 2018, 52 (5) 1801261; DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01261-2018. Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/52/5/1801261

(3) Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Exacerbations [published 2020 Decl]. In: eTG complete [digital]. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2019 Jun. Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au.acs.hcn.com.au/viewTopic?topicfile=chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-exacerbations&guidelineName=Respiratory&topicNavigation=navigateTopic

(4) Australian Medicines Handbook. Salbutamol. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; 2020. Last updated Jul 2021. Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://amhonline.amh.net.au.acs.hcn.com.au/chapters/respiratory-drugs/drugs-asthma-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/beta2-agonists/salbutamol?menu=hints

(5) Australian Medicines Handbook. Terbutaline. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; 2020. Last updated Jul 2021. Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://amhonline.amh.net.au.acs.hcn.com.au/chapters/respiratory-drugs/drugs-asthma-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/beta2-agonists/terbutaline?menu=hints

(6) Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Sep 13;2013(9):CD000052. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub3. Accessed 23/08/21, available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24037768/

(7) Walters JA, Tan DJ, White CJ, Gibson PG, Wood-Baker R, Walters EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 1;(9):CD001288. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001288.pub4. Accessed 23/08/21, available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25178099/

(8) Antibiotic management of COPD [published 2019 Apr]. In: eTG complete [digital]. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2019 Jun. Accessed 23/08/21, available from: https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au.acs.hcn.com.au/viewTopic?topicfile=COPD-antibiotic-management§ionId=abg16-c120-s3#toc_d1e73

(9) Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Effect of high flow oxygen on mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in prehospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010 Oct 18;341:c5462. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5462. PMID: 20959284. Accessed 23/08/21, available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20959284/

(10) Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, Picot J, Wedzicha JA, Smith BJ. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 13;7(7):CD004104. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub4. PMID: 28702957. Accessed 23/08/21, available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28702957/

Contributors

Reviewing Consultant/Senior Registrar

Dr Jordan Lai

Dr Asha Bonney